UK medicines regulation: responding to current challenges

- Natalie Richards

- Jan 4, 2017

- 13 min read

The medicines regulatory environment is evolving rapidly in response to the changing environment. Advances in science and technology have led to a vast field of increasingly complicated pharmaceutical and medical device products; increasing globalization of the pharmaceutical industry, advances in digital technology and the internet, changing patient populations, and shifts in society also affect the regulatory environment.

In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) regulates medicines, medical devices and blood products to protect and improve public health, and supports innovation through scientific research and development. It works closely with other bodies in a single medicines network across Europe and takes forward UK health priorities. This paper discusses the range of initiatives in the UK and across Europe to support innovation in medicines regulation. The MHRA leads a number of initiatives, such as the Innovation Office, which helps innovators to navigate the regulatory processes to progress their products or technologies; and simplification of the Clinical Trials Regulations and the Early Access to Medicines Scheme, to bring innovative medicines to patients faster. The Accelerated Access Review will identify reforms to accelerate access for National Health Service patients to innovative medicines and medical technologies. PRIME and Adaptive Pathways initiatives are joint endeavours within the European regulatory community. The MHRA runs spontaneous reporting schemes and works with INTERPOL to tackle counterfeiting and substandard products sold via the internet. The role of the regulator is changing rapidly, with new risk-proportionate, flexible approaches being introduced. International collaboration is a key element of the work of regulators, and is set to expand.

The UK regulatory environment

The medicines regulatory environment is undergoing a period of significant evolution, partly in response to the changing environment in which it operates. Advances in science and technology have led to the development of new types of product, with increasing numbers of biopharmaceuticals; biosimilar medicines; advanced therapies (gene therapy, cell therapy, tissue therapy); more personalized treatments and precision medicine; greater convergence between medicines and medical devices; and more combination products – products composed of a combination of a drug or biological product and a device – and products that sit on the borderline between medicines and other sectors, such as food, cosmetics and biocides. The diversity and complexity of products have never been greater. The industries producing pharmaceuticals and medical devices are increasingly global in nature, developing products for global markets.

Manufacture and supply chains are expanding across the globe and becoming more complex, which increases the potential for counterfeit or substandard products to enter the supply chain. Advances in digital technology have opened up opportunities for better regulation of medicines, including opportunities to work together with partners in the health and care system for mutual benefit. However, in addition to this, the advent of the internet has also led to an increase in the illegal supply of pharmacy-only and prescription-only medicines online.

Given the complexity of developing new products, it has been increasingly recognized that regulators play a key role in supporting innovation and facilitating the development of new products. This applies particularly in areas of unmet medical need, whether well-established conditions such as dementia; new and emerging public health threats, such as Ebola or Zika virus infections; or antimicrobial resistance.

The cost of developing a new product is estimated to be in the order of £1.15 billion and takes around 12.5 years [2], which means that they must be developed optimally from the beginning. In addition, given these huge costs, burden reduction has become a key governmental priority.

Furthermore, the population using medicines and devices is changing; we are seeing a shift towards an older patient population with multiple comorbidities and chronic conditions, and increased numbers being treated with polypharmacy. This leads to increased levels of confounding factors to be taken into account when assessing the effect of a medicine on the human body.

Shifts in society are driving the way that patients and the public perceive the regulator; expectations are becoming higher and greater transparency is required to address these concerns. Decisions made by regulators and governments are often subject to greater scrutiny, criticism and challenge. There is increasing pressure to bring novel therapeutic products to market faster and with less bureaucracy; however, this is also met with a decreasing tolerance for problem products. Patients are beginning to take more ownership of their conditions and treatments, and are becoming better informed as a result of online searches and the ability to link with others using patient group forums.

The UK Government has also set out various priorities which the UK regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) will contribute to taking forward. In the UK, the Strategy for UK Life Sciences was launched by the Prime Minister in December 2011 [3]. This is led by the Office for Life Sciences – part of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and the Department of Health – which champions research, innovation and the use of technology to transform the health and care service. The Life Sciences Strategy highlights a number of areas relevant to the MHRA to support innovation – through transparency and communications; changes in the healthcare system; and regulatory reform and burden reduction – with the overall aim of improving patient access to quality healthcare.

The regulators’ response to these challenges

The role of the MHRA is to regulate medicines, medical devices and blood components for transfusion in the UK. The Agency plays a leading role in protecting and improving public health, and supports innovation through scientific research and development. The MHRA is an executive agency, overseen by the Department of Health, which has oversight of some 14 agencies and partner organizations [4].

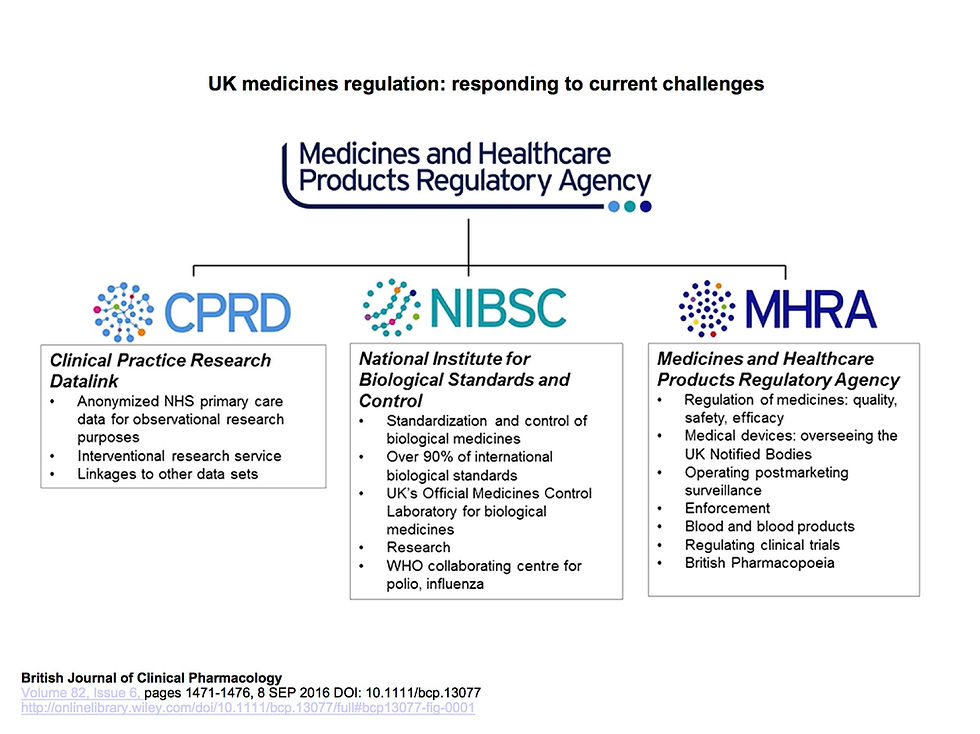

The Agency is made up of three centres (Figure 1): the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), a data research service that aims to improve public health by using anonymized National health Service (NHS) clinical data for research purposes; the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC), a global leader in the standardization and control of biological medicines; and the regulatory centre, which performs the UK's medicines, medical devices and blood components regulatory function, responsible for ensuring their safety, quality and efficacy/performance. The three centres of the Agency work together in synergy to protect and promote public health. The MHRA works very closely with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and other equivalent bodies throughout the EU in a single medicines network.

The MHRA and regulators in Europe, and, indeed, throughout the world, have responded to these various challenges, such that approaches taken to regulation now are very different to those taken in the past. A modern-day regulator must stay at the forefront of new technologies to address innovation drivers, increase patient access to new medicines and remain up to date with new scientific developments to ensure that regulatory science keeps pace with academia.

The MHRA supports innovative product development by various means. Regular horizon scanning is important to identify new science and scientific methods that may have an impact on the regulation of products. The Agency also offers advice in various formats, including helplines, via the Innovation Office; provision of scientific advice or joint advice with other bodies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); or, in the case of regenerative medicines, provides a ‘one-stop shop’ for advice. The Agency also publishes guidance and hosts scientific meetings to keep informed of advancements in a drug's development. It is imperative that the Agency remains an influential body at a European and an international level because of the increasing globalization of the pharmaceutical and device industries, and the supply chain.

The MHRA Innovation Office [5] was set up by MHRA as part of the UK government's industrial strategy for life sciences. The Innovation Office helps organizations that are developing innovative medicines, medical devices or using novel manufacturing processes to navigate the regulatory processes so that they can progress their products or technologies. The Office helps companies, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), academics and individuals who are developing a novel medicine or device, or a novel approach to the development or manufacture of a product, to understand what is required to progress their product through the regulatory processes.

The Office has proven to be successful in encouraging early dialogue between companies or academics and the Agency, and provides regulatory and scientific support to such groups in their interaction with the regulatory environment. Another role of the Innovation Office is to coordinate scientific advice on regenerative medicines/Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) – medicines for human use that are based on gene therapy, cells or tissue engineering [6] – on behalf of all UK regulators (the Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority; the Human Tissue Authority; the Health Research Authority and the MHRA); this is known as the ‘one-stop shop’ for regulatory advice on these products. The Innovation Office has given advice on a wide range of products and technologies, including ATMPs, nanotechnology, stratified medicines, novel drug/device combinations and advanced manufacturing.

To help to illustrate the work of the MHRA's support for innovation, the Agency has published a series of case studies [7]. These examples include helping manufacturers or academic researchers with novel manufacturing approaches and factory layout; for instance, the Agency provided advice to a company building a factory to manufacture a novel drug–device combination product, to ensure that they fully understood the manufacturing challenges and what they would need to do to develop and build the new facility, so that they could manufacture their product and bring it to market as early as possible. Providing advice on future-proofing of European manufacturing facilities is also within the MHRA's capabilities, to ensure that manufacturing facilities continue to remain within Good Manufacturing Practice standards. Advice has also been provided to aid the understanding of toxicology and regulatory requirements to progress novel vaccines or novel therapeutics to man; another case study discusses how the Agency provided feedback, guidance and support to a university with their clinical research project into the development and manufacture of vaccines for some of the world's most virulent diseases, such as malaria, and other diseases, including HIV, tuberculosis, influenza and, most recently, Ebola. Advice has also been given to aid the understanding of the quality and regulatory requirements for cell banks or cell culture facilities – in one case, providing advice on the procurement of stem cells and the regulations surrounding their use. In addition to the work of the Innovation Office, the Agency also holds some 300 scientific advice meetings each year.

Another area of focus of the MHRA is to ensure that the regulatory framework remains fit for purpose and risk proportionate. In this regard, the Agency was involved in the negotiation of the Clinical Trials Regulation, to replace the Clinical Trials Directive, which, although achieving a certain amount, was widely criticized for being over-burdensome. The new regulation is likely to come into force in 2018, and includes various elements that will make the regulatory oversight of clinical trials simpler and more risk proportionate [8]. These include a single EU portal, where a single application process can be made to all European Member States in which the trial is intended to be undertaken, simplifying the application procedure; implementing reporting capability via the EU portal to record key trial milestones; a more risk-based approach, where less stringent rules will apply for subsets of trials termed ‘low-intervention trials’, which have minimal additional risk compared with standard care; and various other altered approaches to streamlining the clinical trial process. It is, of course, critical that regulators and the clinical and academic communities continue to remain vigilant to emerging science and learn from events such as the recent tragedy in France which sadly resulted in the death of a volunteer in a clinical trial. While clinical trials have a very good safety record, regulators and researchers must learn from this tragic event, to see how to prevent such occurrences, however rare, from happening in the future.

Another area of focus nationally has been the holding of scientific meetings to ensure that regulators understand emerging science and can therefore ensure that regulation can keep up with science. The Ministerial Industry Strategy Group (MISG) established forum meetings as a mechanism for bringing together government, industry, the academic and clinical community as well as patients, to discuss areas of rapidly emerging science. The meetings held include new approaches to clinical trial designs, physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling, aspects of regenerative medicine, biomarkers, umbrella and basket trials, personalized medicine, and risk–benefit decision making.

Speeding up patient access to new, promising, innovative treatments in areas of unmet need is a priority for the UK government, regulatory agencies and the pharmaceutical industry. The MHRA's Early Access to Medicines Scheme (EAMS) [9] was launched in April 2014 to give a regulatory opinion to support use, on an unlicensed or off-label basis, to important innovative medicines for patients with life-threatening or seriously debilitating conditions without adequate treatment options. The EAMS scheme follows two stages – firstly, a drug is assigned a new Promising Innovative Medicine (PIM) designation to provide an early indication that a product may be a possible candidate for EAMS; and, secondly, the MHRA issues a new benefit–risk scientific opinion based on the information available at the time of application. The previously existing mechanisms for the use of unlicensed medicines, such as named patient use/compassionate use, are still in place; however, the EAMS scheme has the advantage of a robust regulatory decision to support such use.

To date, there have been 17 PIM designations and eight positive benefit–risk scientific opinions granted in areas such as oncology and heart failure.

The Accelerated Access Review (AAR) [10] in the UK is an independent review, initiated in 2015, which aims to make recommendations to Government on reforms to accelerate access for NHS patients to innovative medicines and medical technologies. Three potential areas of reform have been identified: regulation, reimbursement and uptake. An interim report was delivered in October 2015 which made five propositions: to put the patient centre-stage; getting ahead of the curve; supporting all innovators; galvanizing the NHS; and delivering change. The final report is due to be published in autumn 2016 and is eagerly awaited. The outcome of the review should result in the UK health system being more effective, efficient and supportive of innovation, with patients being able to access more effective, affordable, cutting-edge innovative treatments and achieving better health.

There are various factors relevant to medicines regulation and the MHRA which were identified in the interim report; these include the patient role in clinical trial development and risk–benefit decisions; novel clinical trial methodologies; a ‘how-to’ guide on accelerated development pathway; new devices designation; closer working with other regulators; and the development of regulatory science. While this is a review commissioned by English health ministers, and will largely cover the English environment, there may be recommendations that will need to be taken forward into discussions with other regulators in a European environment. Indeed, it is possible that some of the current EU initiatives (see below) may address some of the areas to be recommended for change in the review.

It is important to remember that the pharmaceutical industry is a global industry, and that the medicines legislation within which the UK operates is, in fact, Europe-wide legislation. The MHRA works closely with the European regulator, the EMA, in many of its activities.

A medicine can be licensed just in the UK, in certain European countries or Europe-wide [11]. Most new active substances are licensed via the centralized procedure, with the EMA coordinating the assessment. Regulators from each Member State across Europe collaborate to assess licence applications and other regulatory activities, including pharmacovigilance and signal detection. This process results in a licence being granted across the whole of Europe. The MHRA may be asked to take the lead on the licensing process in Europe, particularly for biological and biotechnology treatments, as this is an area in which the MHRA has particular expertise, but also in any other areas. Many of the regulatory activities to foster innovation and advancement of new therapeutic approaches today are, in fact, joint endeavours within the European regulatory community.

Support for innovation and using regulatory flexibilities is also a key priority for the EMA, which launched a pilot in March 2014 to make proactive use of these flexibilities (such as conditional approval, licensing with conditions, licensing under exceptional circumstances, accelerated assessment), known as adaptive pathways [12]. The adaptive pathways model is based on three principles, the first of which is iterative development. A product is either given approval in stages, starting off in a well-defined patient subgroup with a high medical need and then expanded to wider patient populations, or its benefit–risk profile is determined following conditional approval using early data and surrogate endpoints to predict clinical outcomes. The second principle involves the gathering of real-world postauthorization evidence in real time to supplement clinical trial data. The third principle comprises stakeholder engagement early on a medicine's development, to explore options in a ‘safe-harbour’ environment, to consider detailed technical and scientific questions based on concrete examples.

The EMA has also launched a new voluntary scheme to boost the development of priority medicines to meet an unmet medical need, and patients' access to these: the PRIority MEdicines or PRIME scheme [13]. The scheme involves early discussions and greater interaction between the regulators and the developers of promising medicines, with early appointment of rapporteurs, involvement of multidisciplinary groups of experts to give guidance on the overall development plan and regulatory strategy, scientific advice at key development milestones with the potential involvement of multiple stakeholders, and confirmation of the potential for accelerated assessment at the time of an application for a market authorization. These enhanced interactions will produce more opportunities for finding the optimal path through the regulatory system for efficient drug development and licensing, so that these medicines can reach patients earlier. The scheme is available from proof of concept for companies, or proof of principle for SMEs and academics. To make the most of innovative products, earlier access to them must be balanced against need, information, risk and uncertainty. Early access to innovative medicines must be accompanied by strengthened vigilance to ensure that focus is maintained, to identify any risk at the earliest possible opportunity.

It is important to note that both Adaptive Pathways and PRIME are EU schemes aimed at the optimal development and licensing of new medicines, and are entirely complemented by the UK-only EAMS scheme, which is about use before products are first licensed. It is expected that products under the EAMS scheme will be optimally developed and go on to be licensed once the requisite data have been generated.

The MHRA is recognized as a world leader in adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting; the Yellow Card Scheme [14] marked 50 years in 2014, with over 800 000 ADR reports received to date. Currently, medicines and medical devices have separate regulatory models; however, a joint medicines/devices vigilance strategy is currently being developed. Reporting tools are being simplified to aid better reporting, including a single Yellow Card Scheme portal to receive all adverse reactions and events for medicines and devices, and a new mobile app for reporting ADRs. Strengthened vigilance at the MHRA is also utilizing the CPRD to monitor outcomes, effectiveness and safety in the real world.

To tackle the inherent issues which come with a globalized supply chain and increasing availability of medicines over the internet, the MHRA is working with international partners to implement the Falsified Medicines Directive [15] (FMD). The FMD will enable regulators to strengthen regulatory oversight over an international supply chain, to prevent the entry of falsified medicines into the legal supply chain, and to ensure that any medicines, excipients or starting materials which are sourced from non-EU countries meet EU standards of manufacture. A mandatory common logo (Figure 2) has been introduced which will enable patients and consumers to identify and verify that an online retailer is a legitimate supplier of medicines. Moreover, the introduction of safety features (mandatory seals and unique pack identification) on packaging for certain medicines will provide assurance to healthcare professionals and patients of the authenticity of medicines obtained through healthcare systems where medicines are at risk of being counterfeited.

Comments